Window 14: The Eucharistic Bread.

Window 14: The Eucharistic Bread

The fourteenth window in the Creation and the New Creation series of windows at the church of Saints Leonard and Fergus, Dundee.

As mentioned in The Introduction to these Dundee windows, the Church of Saints Leonard and Fergus forms roughly a diamond shape with the entrance of the church at the bottom ‘corner’ of the diamond and the altar at the opposite ‘corner’. The first window of the series is to the left of the entrance and from there, they progress in a clockwise direction until the last one is reached, located to the right of the entrance.

Opposite the entrance is the altar, the most important feature of the Church and the focal point of Christian worship. The current window, Window 14: The Eucharistic Bread, and the next, Window 15: The Eucharistic Wine, form a pair and are given pride of place either side of the altar; this one is to the left of the altar and is the last of the seven Spring windows and Window 15 is to the right, and is the first of five Summer ones. Their positioning emphasises their importance in this series of 24 windows, and the importance of their subject, the sacrament of the Eucharist. They belong to two themes that weave their way through the series, The Seven Sacraments and The Days of Creation.

The Eucharist was instituted by Jesus at the Last Supper on the eve of his crucifixion. During this meal he gave his disciples bread – which he called his body – and wine – which he called his blood. He told his followers to ‘do this in remembrance of me’ (see Luke 22.19-20). During the sacrament of the Eucharist, the bread and wine are consecrated, or made sacred, transforming the basic elements into the presence of Christ. Christians differ on how, exactly, Christ is present in the bread and wine of the Eucharist, and within the Catholic Church the bread and wine are believed to be transformed into the body and blood of Jesus Christ, a doctrine known as transubstantiation.

In designing these two windows, Dad made the deliberate decision to emphasise the human involvement in the eucharistic bread and wine by designing the windows to contain a field of wheat and a baker in the one, and a grapevine and a grape-picker in the other. In doing so, he was reflecting the changes made to the liturgy during the Vatican II reforms of the 1960s. The Offertory prayers, spoken when the priest elevates and consecrates the bread and wine, contain the words ‘work of human hands’ in the post-Vatican II liturgy whereas the traditional liturgy makes no reference to human involvement.

With regard to The Days of Creation theme, the Eucharistic windows symbolise the Sabbath, the day on which God rested. There are intentionally no visual images of this day in these windows. Rather, Dad

treated the two Eucharistic windows either side of the altar as representative of the Day of Rest because traditionally Christians attend Mass and receive Holy Communion on the Sabbath.

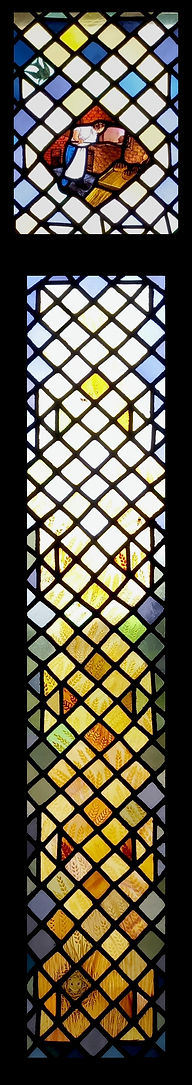

The eucharistic bread, or communion host, depicted in a subtle, abstract way with five white seedy quarries.

Window 14: The Eucharistic Bread is represented by a field of wheat ripening in the sun, wheat being the ingredient of the eucharistic bread. From top to bottom, the window is filled with acid-etched ears of wheat blowing gently in the breeze, the effect of which is quite breathtaking. Summer colours of warm golds dominating the Celtic latticework pattern with flecks of the green of Spring dotted around. By using predominantly acid-etching in this window (and in the next), which has a shimmering, elusive quality, Dad emphasises something of the mystery and awe inspired by the sacrament of the Eucharist itself. Similarly, to draw attention to the special nature of the Eucharist, this window and the next are the only two in the series that have borders around them. The borders are in shades of blue, to contrast with the glowing golden colours of the latticework pattern in both windows. The blues in both cases connect to the shades of blue in their neighbouring windows.

The eucharistic bread, also called the communion host or simply the host, traditionally looks like a thin, round wafer, often stamped with the letters IHS, representing the name ‘Jesus’. Originally Fr McInally requested a realistic portrayal of a communion host in the transom of this window but as Dad had already depicted the moon in the transom of Window 12: Reconciliation just two windows beforehand he didn’t like that idea, because the moon and host would look too similar. Instead, he portrayed the host in a subtle, abstract way as a cross of five white seedy quarries (diamonds) in the field of wheat, towards the top of the main window that shimmer and sparkle in the sunlight. This simple representation of the communion host is also a reference to the five wounds of Jesus. This connects back to Window 2: The Resurrection which contains a stylised form of a Paschal candle with five grains of incense embedded in the candle standing for the five wounds of Jesus.

At the bottom of the window, snuggled into a cosy nest in the wheatfield, is a tiny field mouse, the only painted detail in the main window (apart from a couple of honeybees). It was added at Fr McInally’s request as a reference to the famous Scottish poet Robert (Rabbie) Burns, keeping the Scottish theme in the windows going. The mouse is the ‘wee, tim’rous beastie’ of Burns’ poem, To a Mouse, written in 1785. Along with the mountain hare in Window 13: Saints Peter and Andrew, this mouse represents to the sixth day of Creation in The Days of Creation theme on which God created ‘wild animals of the earth’ (Genesis 1.24).

Rabbie Burns' 'wee tim'rous beastie' snuggled into a cosy nest in a field of wheat.

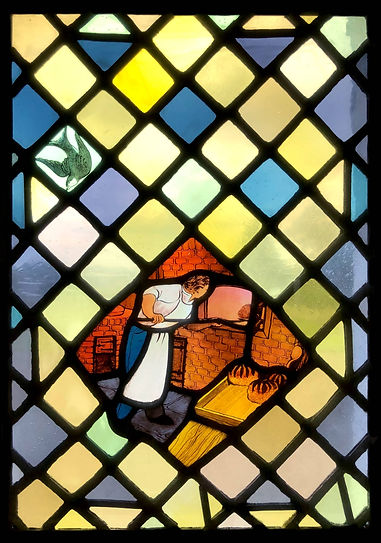

A traditional baker and a single swallow in the transom.

In the transom Dad painted a traditional baker taking a loaf of bread out of the oven, which connects to the field of wheat in the main window and emphasises the human involvement in the eucharistic bread. When the host is elevated to be consecrated during the Offertory prayers, the priest says, ‘…through your goodness we have received the bread we offer you: fruit of the earth and work of human hands, it will become for us the bread of life’.

The bakery scene is based on an oil painting Dad did in the 1970s of the traditional bread oven at Sarehole Mill, an 18th century water mill (see the painting here). The inclusion of Sarehole Mill’s bread oven in the window was a touch of home for Dad as the Mill is only five minutes’ walk from where he (still) lives and works. Sarehole Mill is now more famous for its association with the author J.R.R. Tolkien and inspiration behind The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy. The baker is none other than Dad himself, which isn’t surprising, given how much Dad loves a good hand-baked loaf of bread!

Flying high up above the baker is a swallow, swallows being regarded as heralds of summer. However, it is a single swallow, a tongue in cheek reference to a quote from Aristotle that ‘one swallow does not make a summer’, a reminder that this is, after all, the final window of the Spring series.

The next window continues the theme of the sacrament of the Eucharist with a focus on the eucharistic wine.